Mental Toughness

Let’s have a look at Ding Liren’s journey in this world championship match against Ian Nepomniachtchi:

First game: Defended a difficult position. Was losing a pawn in the ending, but survived to DRAW. Score: 0.5-0.5.

Second game: Played the ‘creative’ 4.h3. Poor play resulted in a painful LOSS with white pieces in just 29 moves. Score: 0.5-1.5.

Third game: Uneventful DRAW. Score: 1-2.

Fourth game: Played a masterly game, sacrificing first a pawn and then an exchange, to score a memorable WIN. Score: 2-2.

Fifth game: Was outplayed in a nice positional game and LOST – the ‘light squares game’. Score: 2-3.

Sixth game: Bounced back immediately. Outplayed Nepo in a nice positional WIN – the ‘dark squares game’. Score: 3-3.

Seventh game: Sacrificed an exchange in a difficult French defence and held equality, but missed finding his way in critical moments and LOST. Score: 3-4.

Eighth game: Played creatively and held a winning advantage throughout the middlegame, but missed playing correctly in many critical moments. Nepo escaped with a DRAW. Score: 3.5-4.5.

Ninth game: An almost uneventful DRAW. Score: 4-5.

Tenth game: Uneventful DRAW. Score: 4.5-5.5.

Eleventh game: Uneventful DRAW. Score: 5-6.

Twelfth game: Artificial sharp play in the opening – middlegame transition. Was staring at a loss for most of the middlegame, survived and even WON after Nepo missed a definitely easy win. A loss would have almost meant the end of the match. Score: 6-6.

Thirteenth game: Held his nerve to draw a difficult but complex ending to DRAW. Score: 6.5-6.5.

Fourteenth game: Survived some anxious moments in the ending but secured a DRAW eventually. Score: 7-7.

Tiebreaks:

First game: Looked in some trouble but defended tenaciously to DRAW.

Second game: Was in a little trouble in the middlegame but Nepo didn’t use his chances well. DRAW

Third game: Uneventful DRAW.

Fourth game: Topsy turvy! Emerged from opening slightly better. Wrong pawn sacrifice but probably not serious enough troubles in a rapid game. Kept up the pressure in the ending. With just a minute or so on the clock for both the players, started playing confidently and secured a WIN in a hard-earned 68 move endgame.

In a 14 game match, Ding was behind in score in a total of eight games when he actually sat down to play. Eight games! What a mental strength it needs to come out of such odds to win a world championship! (And let us not forget that to reach the world championship itself was dramatic for Ding, after so many things had to go correctly for him to reach the candidates itself. Look up the first blog on his journey to the world championship: prochesstraining.com

Ding Liren – ninth time lucky. Picture courtesy: Stev Bonhage / FIDE

When the contestants reached the tiebreaker after a level score of 7-7 at the end of the regular match, chess lovers probably did not know what to expect. What was that one quality which could be exhibited by one of the players to finally secure the crown? What has been the defining factor which has enabled the champions to ultimately triumph in world championship matches?

In the history of world championships, Vladimir Kramnik achieved one of the most unthinkable feats when he defeated Garry Kasparov in 2000 with a score of 8.5-6.5. Kasparov later gave an insight about Kramnik’s play in the match, “Kramnik designed… a great strategy, to drag me from the territories where I was more comfortable, into the territories where I felt shaky… Like in Tennis, when somebody has a huge serve and then rushes to the net; and someone is playing from the backline waiting for mistakes, and then hitting hard. Kramnik played from the backline.”

Vladimir Kramnik: ‘Playing from the backline’

Kramnik’s backline was resurrecting the Berlin Defence of the Ruy Lopez, which Kasparov failed to crack. And that darn opening has still not been cracked!

Vishy Anand started his match against Veselin Topalov at Sofia in 2010 disastrously. After the fiasco of a long road trip of 40 hours and a blunder in the first game just out of the opening, Anand started the match with a score of 0-1, Topalov gaining the point from the white side of a Grunfeld defence almost without making a single move on his own.

How did Anand come back into the match? Kramnik famously said during the match, “If Topalov needs to make five only moves in a row, he will find them, but if he needs to choose between optically equal alternatives in a strategic position, he is more likely to make mistakes.” Anand and his team found the best way to make Topalov choose between such optically equal alternatives – using ‘little ideas’ in the openings.

Vishy Anand: ‘Little ideas’

What were these ‘little ideas’? These were intended to be of surprise value more than anything – they would not entirely refute or better a line, but force the opponent to play precisely in strategic positions which would not suit his style. It worked like a charm in three decisive games: the third, fifth and the twelfth.

So, what was that one big secret behind Ding’s success at Astana? Tenacity for sure. It is not simply possible for a regular chess player (or a human being) to stare at defeat just inches away so many times in a match, especially in the twelfth game, survive, and still win the match. And what was the moment when it got amplified for all of us to see? Definitely, it was in the fourth game of the tiebreak:

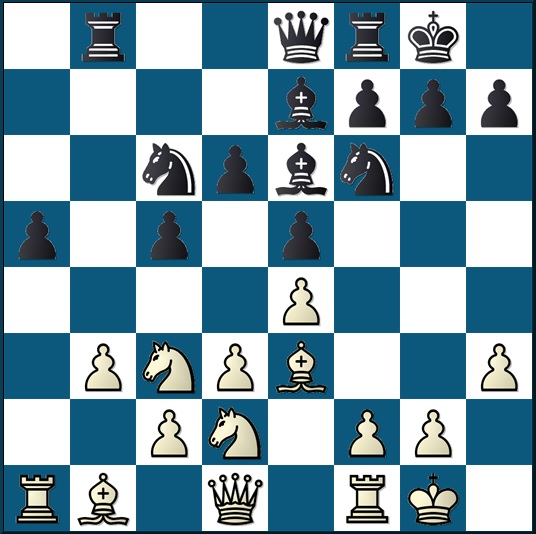

I was following the tiebreak game at the Chessbase India stream hosted by Sagar Shah and Amruta Mokal, where Dommaraju Gukesh was the special guest. It was simply impossible to believe that Nepo would survive this position with white pieces: just look at the bishop on b1! At this point, Guki too was more enthusiastic about Ding’s position, and came up with a profound observation about the players, “Ding Liren is a calculator; Nepo is intuitive”. We were almost sure that Ding would be able to convert this position and win the tiebreak.

But then, Ding suddenly had a rush of blood and sacrificed incorrectly:

There was absolutely no necessity for 29...e4? and once again Ding was back to his usual post in this match: defending.

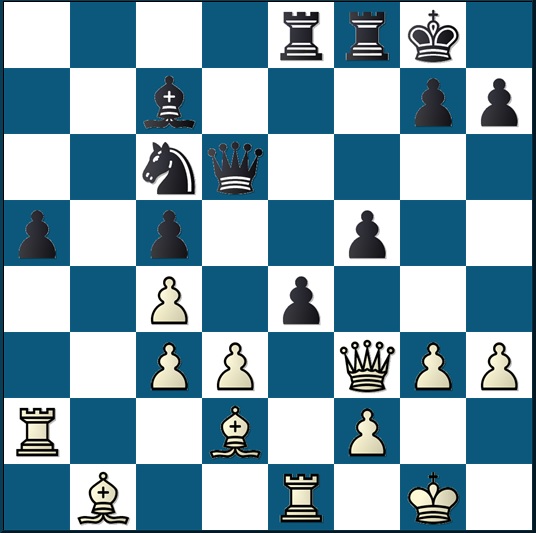

This was the position after Black’s 43rd move, and White started with 44.Qe4+ Kg8 45.Qd5+ Kh7 46.Qe4+ and we were all ready for the game to end in a draw, and preparing mentally for the faster tiebreaks ahead. After all, both the participants had just about a minute and a few seconds each on their clocks at this point. It seemed prudent to draw this game and live another game.

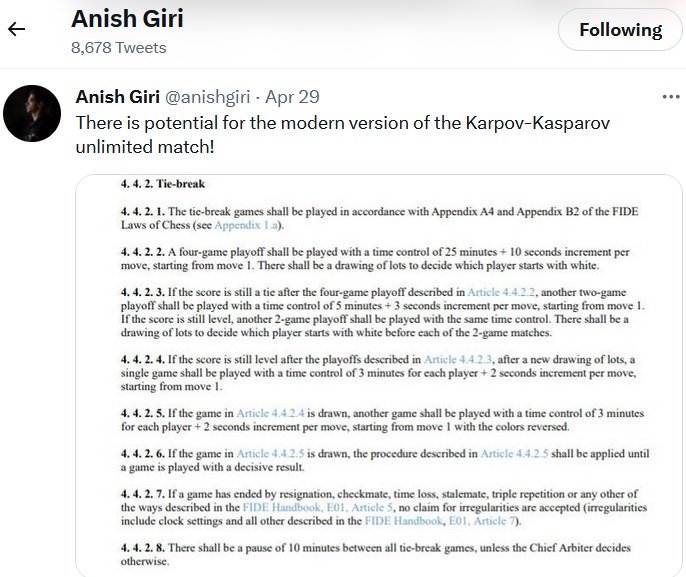

Not to forget, the Nostradamus in Anish Giri had warned of an eventuality of unlimited tiebreak games a couple of days ago:

But unexpectedly, Ding Liren started playing for a win here with 46...Rg6!? He was challenging White to push 47.h4 and is prepared to defend a shaky looking kingside. He was challenging his opponent that he was not afraid of a fight. But more than anything, he showed that one quality which enabled him to survive so many odds and lows to end up in this situation where he could play for the crown of world champion: mental toughness.

A great fight in the tiebreak. Picture courtesy: Stev Bonhage / FIDE

Needless to say, he was rewarded handsomely for his guts. It is even suitable to recall that cliched but applicable quote here, “Fortune favours the brave, especially when you are Alexander Alekhine”.

Hard luck, Ian Nepomniachtchi. You almost had it in your grasp. Congratulations, Ding Liren. You deserve the title of World Chess Champion.