For chess lovers, world championships are always about the combat, the fight. After all, a sport gets elevated to a different level when there are rivalries. Like the legends of Ali – Frazier, Borg – McEnroe, Lakers – Celtics, India – Pakistan (we are talking only the cricket!), Barcelona – Real Madrid and of course, Karpov – Kasparov.

Chess players of 80s and 90s were fortunate that they got to witness two of the greatest players in the history of the game fought each other in five matches. Karpov became one of the world’s elite around 1974, and he kept his high standards of the game till about 1995, whereas Kasparov was literally the best in the world between 1984 to 2005. So, we got about ten years of two rivals at their best, going at each other - not only on the chess board, btw.

We also got fortunate when Kasparov decided to write his ‘My great predecessors’ series where he analysed Karpov’s career in the fifth volume with the brilliant and generous starting heading, ‘God-given Talent’. A goose-bump moment. Any student of the game wishes to learn on positional chess in the post-Fischer era, this is where you start.

We got even more fortunate when he wrote three more books, the ‘Kasparov on modern chess’ series chronicling all his clashes against Karpov. Meticulously written books presenting so much about focus, combativeness and fighting spirit over the chess board. Samples, after Kasparov won the final game at Seville 1987:

“The ovation was undoubtedly the loudest and the most prolonged (roughly 20 minutes) I had ever been awarded outside of my own country. The theatre walls were shaking, and Spanish TV interrupted the broadcast of a football match to switch to the conclusion of our duel.”

“The Seville match clearly showed that chess, like any other creative art, requires a person to give his all. In 1987 I was possibly distracted too much by other matters, I did not allocate my energy properly, and I was unable to concentrate properly on preparations for the match. I am talking about psychological preparations, since I had no complaints about my chess preparations.”

If any student wishes to understand what it takes to be a champion, you need not go further.

In that context, the Ian Nepomniachtchi – Ding Liren match was not expected to be a ‘rivalry special’, though both are perceived quite close to each other in terms of rating and strength. And it was not helpful seeing Magnus Carlsen first playing Poker at a Casino in California, and then the Titled Tuesday at chess.com streaming live, wearing dark glasses (why?) with the Botez sisters dancing in the background (why? Why?)

But just then, the ‘twin strikes’ happened in the fifth and sixth games of the world championship when the rivals traded victories exhibiting that other delightful attraction of the game: creativity.

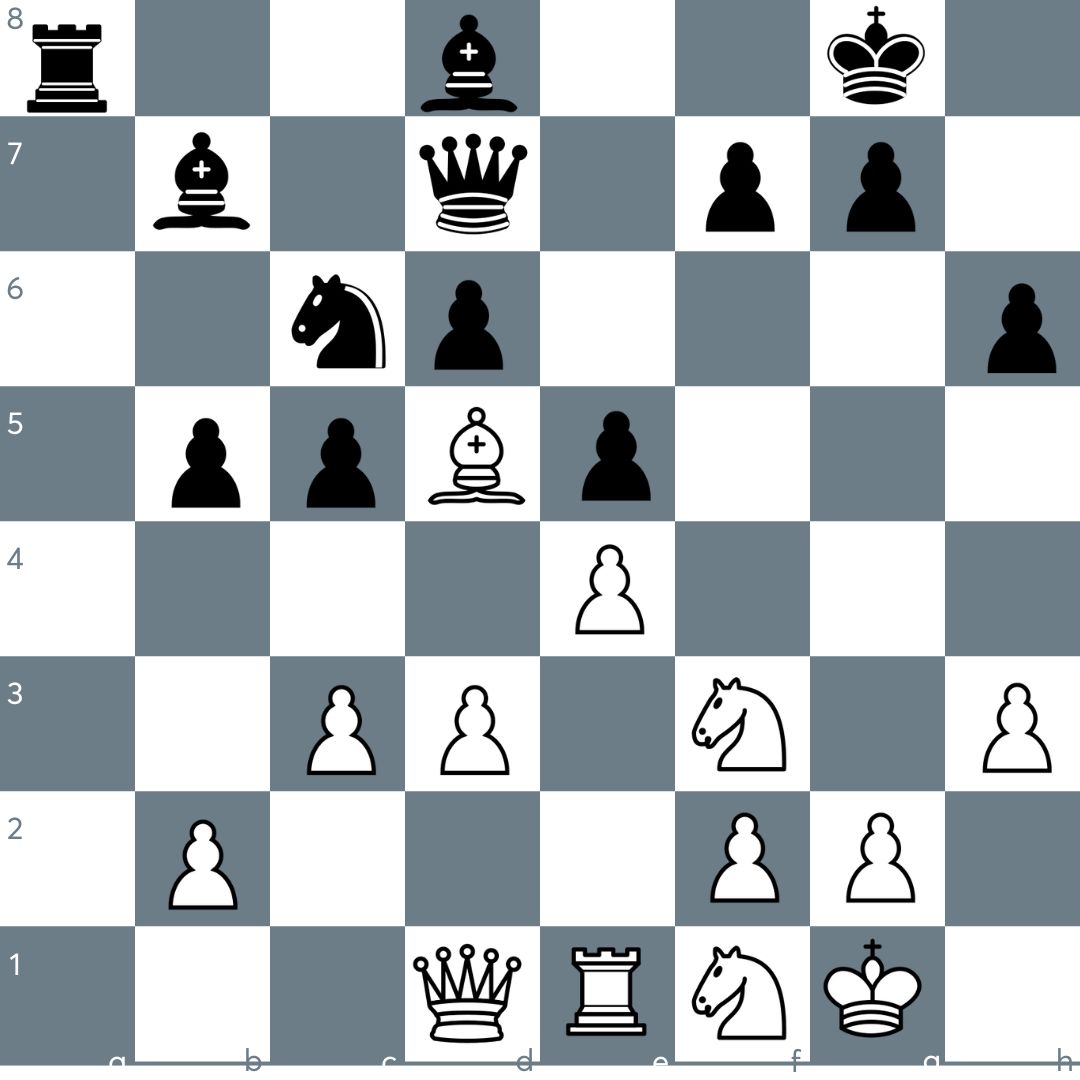

In the fifth game, it was all going quiet when Ding with black pieces made life difficult for himself:

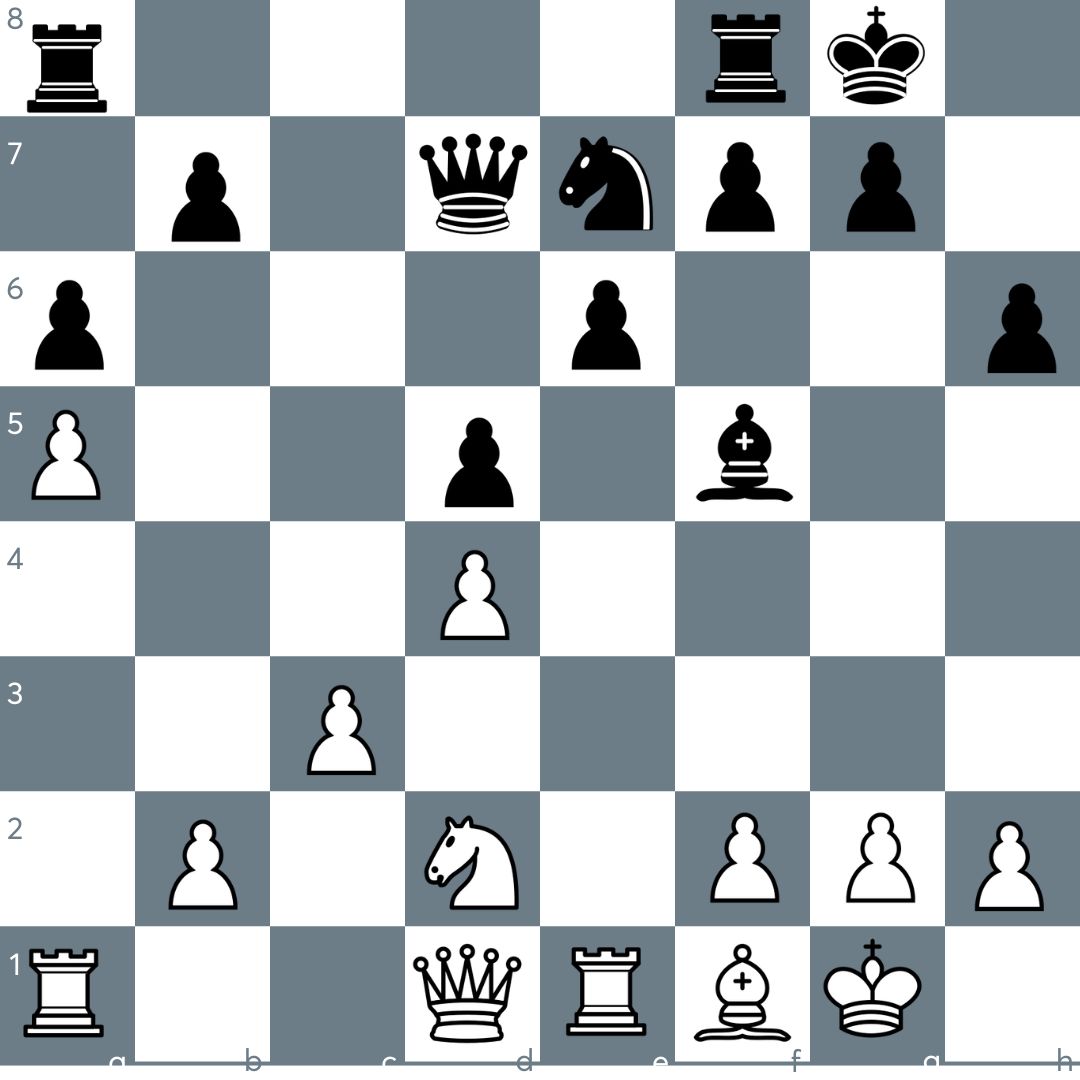

In a typical Ruy Lopez game where the d5-square has to be treated with respect with caution, black played 20...Ne7 exchanging off the light squared bishops. After obvious but instructive play crowned by 23.h4 and 24.h5, Nepo exploited the d5-square and the light square weaknesses and achieved a picturesque position after 33.g4!:

It’s not often that you see such elegance of play and derive aesthetic pleasure looking at the position. In a rare occurrence, Nepo achieved such a delight creating a position so pleasant to look at. He scored a deserving victory in 48 moves.

Ian Nepomniachtchi: rare elegance and aesthetics. Picture courtesy: Anna Shtourman / FIDE.

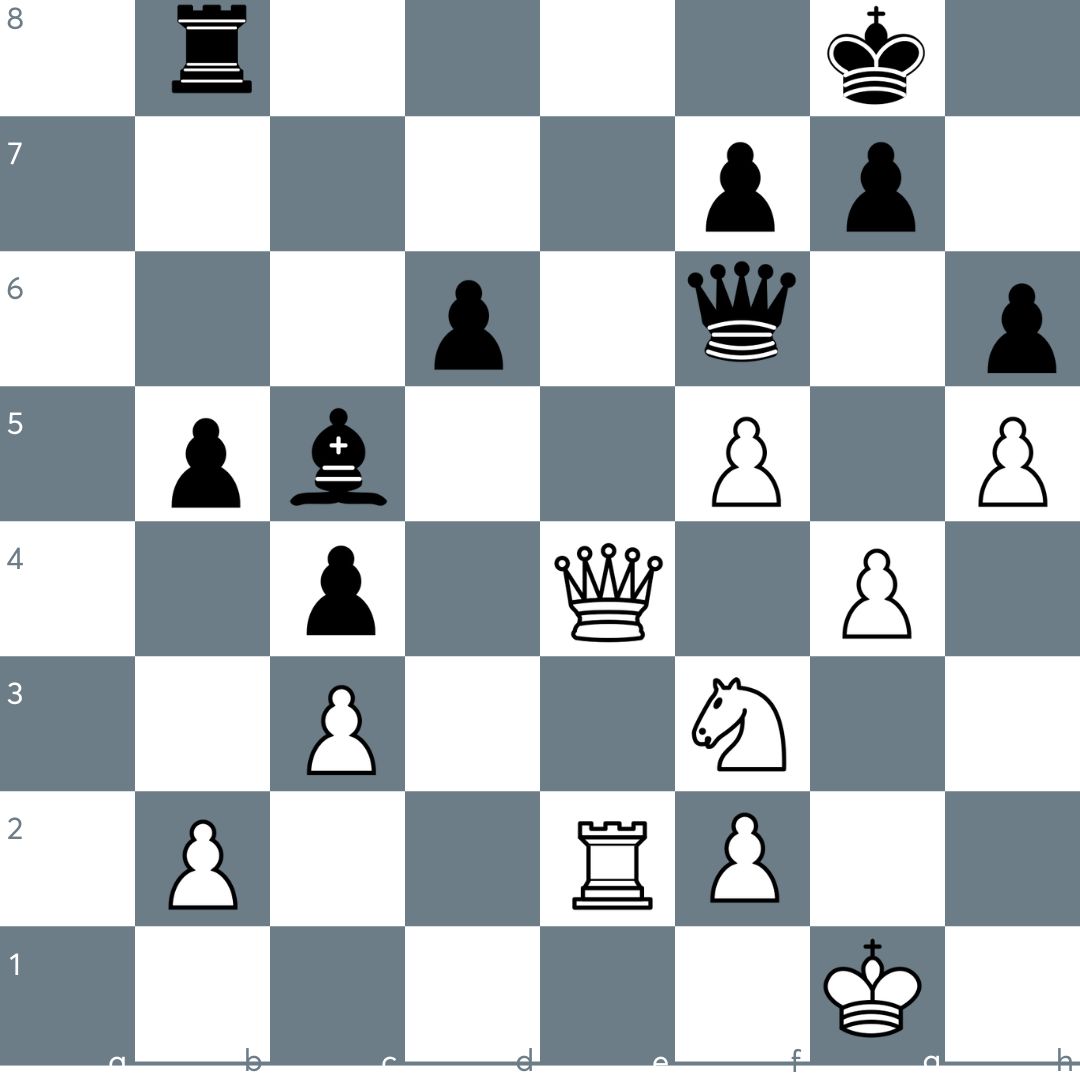

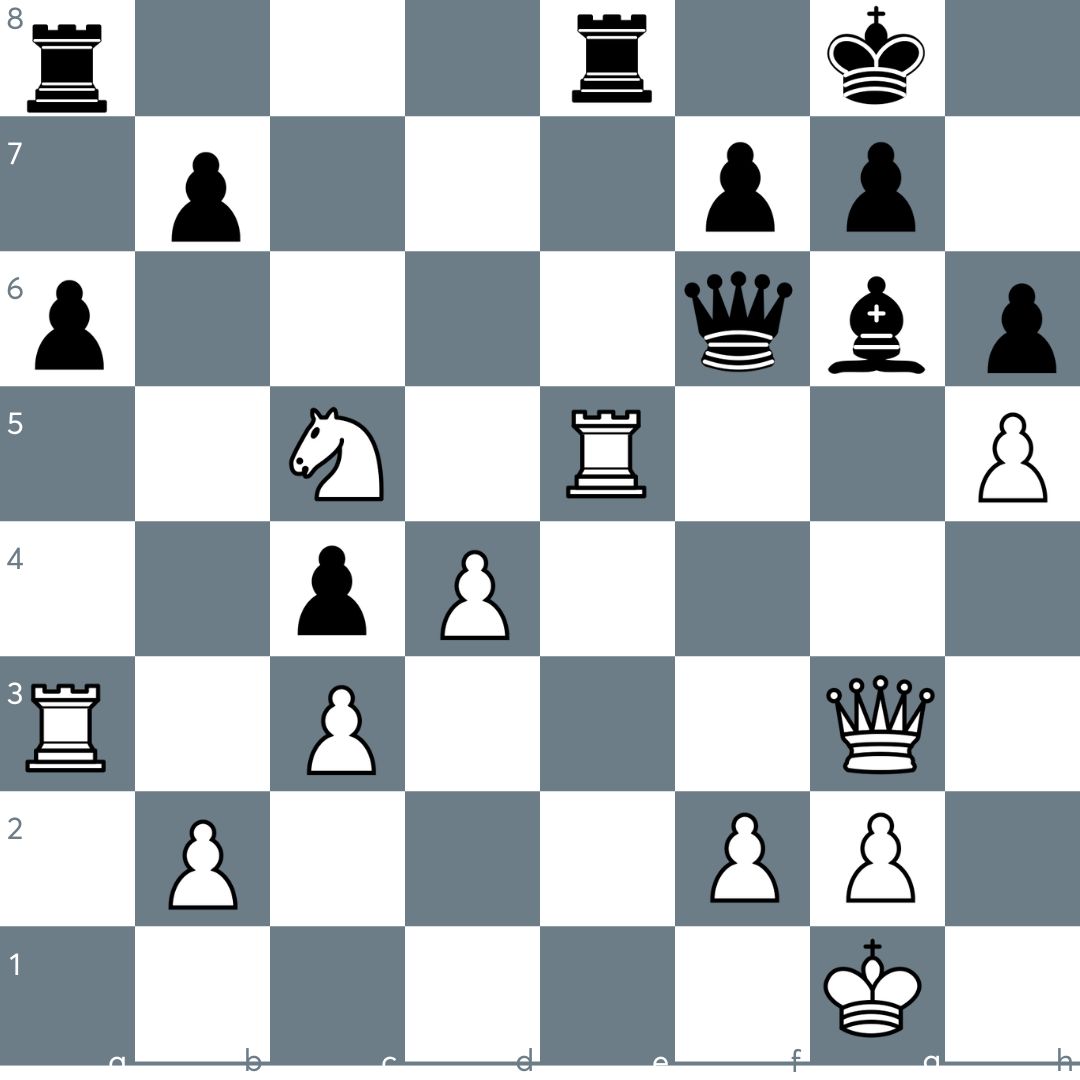

In the very next game, our aesthetic antennae were activated when Ding Liren came up with the pleasing 16.a5:

If the dynamic Nepo preferred the light squares on the centre and the kingside, it seemed Ding preferred to do it on the dark squares on the queenside. It will add to your appreciation when you notice that black’s light squared bishop, proverbially out of the pawn chain, will find it difficult to find any relevance in the game henceforth.

A further moment of beauty came up when Ding managed to achieve 27.h4-h5 also:

Look at the power of the dark side! All Ding’s pieces are occupying the dark squares presenting a certain beauty to the position, though he doesn’t enjoy any clear advantage as yet.

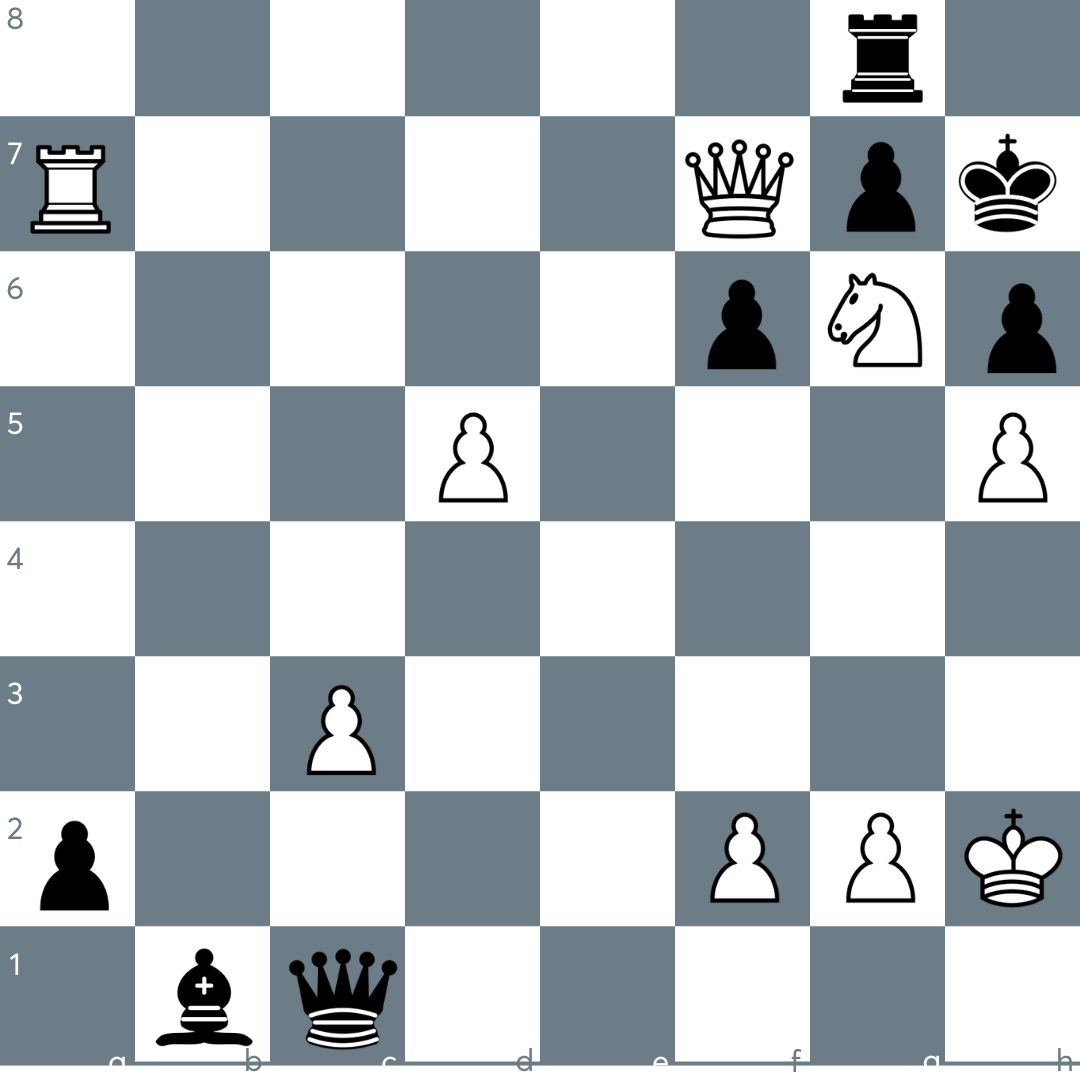

The game finished on an ultimate high in the beauty count:

Even while allowing the black pawn to run all the way to the a2-square, White is threatening the beautiful 45.Qxg8 Kxg8 46.Ra8+ followed by mate on the f8 or h8, forcing Nepo to resign. On spotting the idea, Anish Giri fittingly exclaimed on Ding, “He is a genius!”

Ding Liren – The Genius! Picture courtesy: Stev Bonhage / FIDE.

It is not everyday that one gets to witness the typical combativeness combined with such aesthetically pleasing games in a world championship. Naturally, we are all glued on to the match now.